Aeon Legion: Labyrinth by J.P. Beaubien is the worst book I've ever read in my life.

I was going to start with more of an introduction--a brief tour of other bad books I've read, maybe a snappy metaphor--but I can't even muster up one of those, because this entire thing just baffles me.

First, let's talk about why I read this book.

For over five years, I've been in a book club with a few friends I met through the SmackJeeves webcomic community. The impetus behind the club was simple--one of these friends admitted to not having finished reading a single novel in years. We began with what was a pretty safe bet--Max Brooks's World War Z--and have continued to read an average of nine books a year, ranging from true crime to graphic novels to paranormal romance. Even though we live in four different states and have schedules that prevent us from doing much in the way of anything else together, the book club has cemented itself as a mainstay in our relationship.

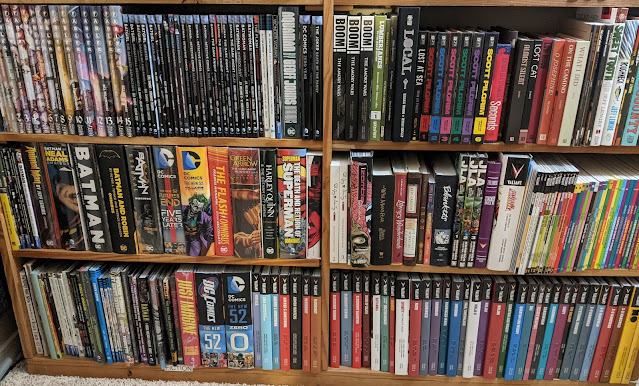

Our selection system is as follows: one member of the club will choose a theme, and every member will select a book that fits. We try to keep the categories broad--teen, nonfiction, books with movie adaptations--to ensure some variety in our choices. When it comes to our individual book choices, we each have a particular M.O. For example, I try to only choose books that I already own, because I always have three-hundred-plus books that I haven't read waiting on my shelves. Another member tries to find books that have been highly rated, to ensure we don't end up with too many duds over the years. And the dear, dear friend that chose our current theme looks for books that will "provide an interesting discussion".

This means she picks bad books almost exclusively.

To her credit, they aren't all awful. Some of them I would even go so far as to call "fine". Books like The Howling, or... well... I'm sure she'll have another one someday.

The current theme is "time", which can be interpreted in a number of ways--seasonal events, aging, multigenerational narratives. But, since our group trends towards speculative fiction, the first book ended up being about time travel. That book was Aeon Legion: Labyrinth by J.P. Beaubien.

Going into this book, I was not aware of Beaubien in any meaningful capacity. It turns out that he is the creator of Terrible Writing Advice, a YouTube channel with over 300,000 subscribers that utilizes a simple animation style and sarcastic delivery with the intent of helping amateur writers improve their craft.

You maybe wondering if this post is written for fans of Beaubien's videos, or for those who dislike them. I know little about the man and his work outside this novel and some cursory research into his other activities, so I don't think having an opinion on him one way or the other going into this breakdown is necessary. My goal is not to attack his character directly, or make definitive statements about a man I don't know personally. However, I will comment a bit on my perception of the author based on my reading of the text. Furthermore, Beaubien's background as a provider of writing advice is crucial to understanding why this book was such a frustrating read. So, with that in mind, let's start with the cover.

The book contains a review blurb on the back from an organization called Best Fantasy Books HQ, which says, "This series redefines exciting (but intelligent) reading." You can decide for yourself at the end of this post if the statement rings true, but I find it interesting that the site this review supposedly comes from seems to have died shortly after the novel was published. I found their website, which seems to not have been updated since 2016 (several articles on the front page are dated for that year). Furthermore, only the main page of the site remains live, and attempting to click on any button, link, or drop-down item redirects to the same message:

So. Let's discuss the book itself.

Aeon Legion: Labyrinth tells the story of Terra Mason, an average twenty-first-century girl who finds herself thrust into the world of the Aeon Legion, a sort of time police in charge of protecting the branching timelines of the universe from numerous foes. Along the way, Terra makes allies and enemies alike and transforms from an aimless American teenager to a brave and adventurous heroine.

Now, based on this description, the novel sounds, at worst, inoffensive. I mean, what's to hate about a classic hero's journey with a bit of time travel thrown in?

But, to reiterate: Aeon Legion: Labyrinth is the worst book I've ever read in my life...

...and I have the receipts.

Let's start with the Nazis.

The novel begins--opening line, even--with Nazis attacking an American library in the year 2000, a result of the time travel experimentation of a Nazi scientist named Hanns. He plans to steal a book on World War II history and bring it back home to 1940-ish, then use the information contained within to help Germany win the war. Our protagonist, Terra, is one of the civilians caught in this event, but the day is quickly saved by Alya Silverwind, a warrior with flowing silver hair, a gleaming sword, and the ability to manipulate time for things like super-speed and... well, mostly that. While Silverwind takes out almost every Nazi, Terra takes this massive distraction as an opportunity to hit Hanns in the head with a rock.

This will turn out to be the most important thing Terra ever does.

You see, this act of bravery--hitting a Nazi with a rock--has made Terra the apple of Silverwind's eye, and Terra is selected to be Silverwind's next squire in the Aeon Legion, the sword-wielding time police that Silverwind is one of the most prominent members of. Silverwind is known for choosing great squires, such as Kairos, a beloved warrior who died long ago and was so influential that there was an entire memorial garden constructed in her name. And how it's Terra's chance to be part of this illustrious lineage.

We'll come back to Terra's adventure in a minute, but I want to follow Hanns for a bit. You see, Hanns was not killed by the dreaded "rock to the head" technique. Nor was he punished, outside of being told not to meddle with time again (which he has been told twice already, apparently). He returns home, and will continue to meddle with time. And during all his Nazi escapades, we are constantly being told one crucial detail: Hanns is not like other Nazis. He may be part of their regime and wish for German victory and worldwide influence, but he has no interest in the persecution and genocide of Jewish people. He merely wants what's best for his country.

THIS IS A PROBLEM.

While I have no doubt that it's possible for a talented author to write a Nazi character with nuance, Beaubien is not a talented author. As such, the take of "not like other Nazis" comes across as, at best, misguided and misinformed--Hanns seems unaware of Hitler's plan to exterminate millions of Jews, despite concentration camps being under construction as early as 1933, and makes no reference to the fact that anti-Jewish sentiments were core tenets of Nazi documents as early as 1920--and, at worst, like the author is taking some sort of Nazi-sympathizing stance. I'm fairly confident the case is the former, and my feeling is that Beaubien's research for these topics consisted of cursory glances at Wikipedia entries without any follow-up digging. However, there are still several troubling passages that should have been rewritten or entirely removed. Of particular note is when Hanns tells Terra that Jewish people are "holding [Germans] back by hoarding all the wealth," and neither Terra nor Beaubien's narration make any attempt to disprove this statement. Instead, Terra merely counters that genocide is not an acceptable solution to this problem, implying that the problem itself is still a valid one, just inappropriately handled.

In 2016, Hanns's "not like other Nazis" character distinction is poorly-handled and uncomfortable. In a post-Trump America, it's straight-up dangerous.

Okay. Back to Terra.

After some absolutely laughable dialogue with her cardboard parents--the sentence "This family prospered because of my determination and your father's self sacrifice" is uttered in complete sincerity--and a brief trip to 1933 to watch Franklin Roosevelt's inauguration--Terra is fascinated by FDR, a detail that is promptly forgotten after this scene--she is taken to Saturn City, a land out of time that houses the Aeon Legion Academy, among other things. This city, and the legion itself, are obviously Beaubien's pride and joy. Chapter V (the author really likes ancient Roman culture) is pages and pages of Terra observing the folks of Saturn City as they assess visitors, praise Silverwind (turns out she's one of twelve heroes called the Legendary Blades), and make reference to numerous people, places, and concepts that the reader mostly has no use or context for. Silverwind abruptly abandons Terra to find her own way into the Academy, because Silverwind's core personality trait is that she is carefree to a fault--flighty, one might say.

Despite having little guidance, Terra is able to find her way to the Academy and secure a spot in its current class not due to her status as a squire, but because she hit a Nazi with a rock. She has shown herself to be brave, but also very determined, refusing to back down when the heads of the Academy tell her she's not good enough to make it. She is stubborn--like a rock, one might say.

Once she's accepted into the Academy, she is given a shieldwatch, a device that strengthens her connection with time and will eventually allow her to manipulate time and even restore people and places to previous states should they become damaged. During her classes--during which almost nothing is ever taught, with the "instructors" instead telling the class to do something and then waiting for them to figure it out on their own--Terra shows little aptitude for anything, but continues to stubbornly hang on throughout each trial she faces. She's not like Hikari, who is innately talented but has a fiery temper, or Roland, who is a master manipulator but also flows like water when he moves.

Have you caught on yet?

Now, there's nothing inherently wrong with comparing your characters to elements, or any other simile for that matter. There's also nothing wrong with choosing a name that references a character's core trait. The problem lies in Beaubien's unwillingness (or inability) to describe his characters as anything other than their singular trait. Terra (which means "earth") Mason (someone who works with stone) is never described as anything other than stone, rock, or iron. She is always stubborn, unmoving, unfeeling, enduring. Alya (which means "sky") Silverwind is always quick, aloof, and unable to be pinned down. Hikari (which means "light") is always bold, violent, and temperamental. And Roland (whose last name is revealed in the final chapter to be Delmare, meaning "of the sea") is always flowing and graceful, even when he's busy being a dirty, dirty cheater (we'll get to that).

Again, you can do this sometimes. Think about the Harry Potter series, where every name is meticulously constructed. Yes, Sirius Black is named for the dog constellation, has a canine Animagus form, and is loyal to a fault. But he's also a complex man with protective instincts and reckless impulses, a quiet intelligence and a bold streak, family riches and twelve years lost to Azkaban. Beaubien's characters lack anything but their single defining trait (excluding the few times when Terra throws out snappy one-liners after action sequences, despite having nothing approaching a wit at any other point in the story).

Speaking of dog men, the head of the Legion is a man named Lycus ("wolf") Cerberus (self-explanatory) who is described as having a "wolfish" or "wolf like [sic]" grin no less than seven times. We counted.

Now, at this point, I need to admit something. Up until Terra reached the Academy, I thought there was about a ten-percent chance this book was a parody. Having been made aware of Beaubien's YouTube career, I thought that an intentionally atrocious book might serve as some sort of teaching device in service of his wider strategy. It wasn't until I got about a quarter of the way into the book that I realized he was out of time to pull the surprise reveal, and that the book was going to be every bit as awful all the way through.

During her tenure at the Academy, Terra and the other "tiros" (one of many terms borrowed from ancient Rome, meaning "beginner") are awarded points based on their performance. Points are exchanged for new weapons, and can be traded through the Trial of Blades, a system of formal duels that Hikari apparently spends her entire free time engaging in. Tiros who end a week with zero points are cast out of the Academy and returned home. Thankfully, Terra manages to hang on to at least one point due to her unflinching determination.

Or, you know, that would be the case if there was any sense of consistency in this book. It would be cheesy and predictable, but at least it would be in line with the characterizations being presented.

However, as the pre-chapter excerpts from Cerberus's notes tell us, the points system is a trick! Points are given out in such a way to ensure that recruits like Terra who need a little extra time are able to hang on. This could be a good twist, and possibly a commentary on the difference between hard work and natural talent, except for two small issues.

The first is that Cerberus's pre-chapter notes come way too early. By that, I mean that the reader is explicitly told the points are a lie well before the chapter where Terra will eventually learn this herself. It's explicitly stated that points totals should be manipulated to favor recruits like Terra, so we the readers couldn't care less what her point total becomes over the next several chapters. This is a structural choice the author makes several times, repeatedly robbing his readers of any suspense.

The second problem with the points reveal is that most other tests in the book also have twist endings.

When Terra first becomes a tiro, the recruits are offered the chance to participate in three different trials. Completion of each one will earn them a point, but the tests are all optional. Terra attempts--and fails--all three, but once the trials are over, her instructor reveals that the real test was to at least attempt each of the three trials, regardless of success or failure. This means that even though Terra has no skill in any of the trials (actually, she's a good climber, but like many other details this hardly matters), she still succeeds through being stubborn enough to at least try them. Then, later, the tiros are dropped into the Cretaceous period and forced to survive. Terra is abducted by a group of enemy soldiers that torture her before it's revealed that they're just other Aeon Legion members testing them. This one doesn't necessarily nullify the test itself, but it does mean the reader is trained to expect these "surprise" revelations.

The fact that the points are manipulated is revealed partway through Terra's training, but it isn't until Terra is about to enter the Labyrinth--the final collection of twelve trials that will determine if she becomes a super-special time cop--that she's told that not only are the points manipulated, they don't matter at all. It's a double twist! At this point, it's kind of like watching an M. Night Shyamalan marathon--the reveals would be less predictable if there weren't so many of them in a row.

Terra, as I mentioned earlier, is not the only recruit being tested for time-cop status. Far from it, as there are actually thousands of tiros undergoing this rigorous training. You have Hikari, the talented-yet-brash warrior from Feudal Japan, who is better than almost everyone at almost everything--combat, agility, driving (we'll get to that). There's also Roland, a knight of Charlemagne with a silver tongue who isn't afraid to lie or cheat to succeed. Rounding out the core group of heroes is Zaid, who is the only named POC besides Hikari that I can confirm is not white.

And... that's about it. I guess there's Vand, a bully who gets his neck snapped in a comically-edgy demonstration of the shieldwatch's restorative capabilities before being kicked out. And a couple one-off tiros who are only named when it is needed for them to speak. But it wasn't until I was told during the final chapter that there were thousands of tiros at the start that I knew there were thousands of tiros at the start. The Academy, for all its supposed glory, mostly felt like a giant empty coliseum for Terra and her three named allies to come into their own as requisite heroes.

It becomes apparent over the course of several tests that Terra's class is Special. Almost every single time she or one of her few named classmates completes a task, it's noted how unusual it is for them to perform so well.

Page 118, when Roland is able to push his instructor off a platform.

Page 128, when Terra manages to... stand the way her teacher tells her to (this one physically hurt my friend who took basic martial arts classes).

Page 151, right before Terra completes the course in question.

Page 237, after an elaborate group exercise.

If the Aeon Legion is so bad at choosing initiates that this is where the bar is set, I truly fear for the spacetime continuum.

And yet, despite the recruits repeatedly exceeding expectations in the most banal ways imaginable, one of the instructors comments, "I swear this group seems slower than last year's and I don't know how that's possible." The statement is wildly inaccurate considering Terra, Hikari, and Roland are doing things that nobody has done in several recruitment cycles. However, it brings up an interesting point: this place, which apparently tests thousands of recruits a year (a concept that seems completely useless in a city that exists outside of time, but don't get me started on that), has no noteworthy students to speak of besides Kairos and our handful of named tiros from this apparently exceptional batch. It's almost like Beaubien is unable to hide the fact that the Academy has no historical function within his elaborate world, and only exists as a way to show off his main characters and get the readers to believe them to be destined for greatness.

I've read plenty of young adult novels in my time (and believe me, this book is YA through and through, despite only being advertised as science fiction), and I know that it's very common for the protagonist to succeed through unconventional means. It's a way of appealing to the outsiders, the kids who don't feel like the typical path to success is viable for them. And that's commendable. But there's a big difference between a character who finds their own route to the top of the mountain and a mountain that is constantly rearranging itself to create a straight path for the protagonist. And that's what this book is doing--changing its rules and tying itself in pretzels to make it make sense that someone whose entire characterization is her ability to let things happen to her is successful.

Ultimately, I think, the book's biggest conceptual flaw is Terra's sole trait of endurance--which, to be clear, is different from stubbornness. Beaubien could have made a character who is hard-headed and bold, and propels themself through barriers to achieve success. Which he did. But it's Hikari. He could have also made a character who knows they can't succeed through traditional means, but are crafty enough to find their own solutions even if other people frown on their methods. Which he did. But it's Roland.

Instead, Beaubien chose to make his central character someone whose defining trait is passive. You cannot act on endurance, because endurance is merely the state of resisting other actions being thrust upon you. To that end, Terra has almost no agency in her own story. Scenes are frequently constructed by having Terra watch as someone else does something exciting, or having her be told what is going to happen next. She is a lens for us to watch the story through, but not someone we are experiencing the story with. She mostly sits there while the action happens around her.

This is why, not only did I find the other characters more engaging (albeit only mildly, since they were also borne of feeble one-word characterizations), I rooted for them at the expense of Terra. In particular, I (and the rest of my book club) found Roland to be the one most likeable tiro. He can be a bit of a sly scoundrel, but he's also intelligent enough to recognize that the Academy is full of tricks anyways, so why not work a few of his own? In one scene, the tiros are tasked with disassembling, cleaning, and reassembling aeon edges, which are the fancy time swords like Silverwind uses. However, the wording of the task is merely to present a clean blade to the instructor at the end of the day. Roland does exactly that, by taking a clean blade off the rack and giving it to the teacher.

And Terra hates this.

Throughout the book, Terra is constantly aggravated at Roland's flippancy towards rules and honor. She berates him for lying about his past, and for the "sneaky" way he completes tasks--such as in an early test where he waits for the other recruits to try and fail to cross a series of ice floes, taking note of their mistakes before making his own attempt. I think it's fair to say that most readers would consider this a pretty smart way to solve the problem, especially considering Terra is one of the last recruits to attempt the firey obstacle course, the combat over water test, and the glacier climb, after watching most of the other recruits fail or the obstacles burn away. The only difference between Roland and Terra in these instances is that Terra hesistates because she is bad at things, and Roland hesitates because he's strategic. This double standard is not acknowledged, however, and Terra, for whatever reason, thinks Roland's wait-and-see approach--and every other instance of him using his wits--is shameful. And since the author knows nothing of nuance, we are meant to take this same stance and denounce Roland as a scoundrel.

But my book club actually came to realize that Roland is the most interesting, relatable, and well-rounded character in the entire story, and lamented that he wasn't the protagonist. Because, especially in terms of the blade cleaning, Roland's right. He's playing the game the same way the Academy is playing him.

And Beaubien doesn't acknowledge this. There is no scene that confirms this to be the "true" test in the way Terra passes the "true" test of just attempting things. Nope, it's just Roland "cheating" on a task, full stop, full double standard.

Maybe he didn't realize what he'd done here. That he had telegraphed another "test within a test" and then not followed up on it because it wasn't Terra that would benefit. Or maybe he was catching onto the fact that he was leaning on the twist-ending tests too much.

But it comes across to me like he's projecting his own insecurities and completely unaware of it.

To be clear: I don't know a thing about Beaubien outside the text of this novel and about ninety seconds of one of his videos I watched after finishing the book. But between how he tries to paint Roland as someone to wag a finger at, and how Terra manages to be the most successful student despite having hardly any discernible skill or talent, and how hardly anybody believes in her... I'm reading this as someone who is still working out some troubles they had during their school years, and has taken to writing a dream scenario where past hardships can be reworked into heroic successes. I won't speculate on the specifics of Beaubien's childhood, but between the vaguely strawman inserts (Roland, one of the most competent tiros who is despised because he uses his wits better than Terra and later gets "punished" with forced squireship instead of a cushy job) and the negatively-stereotyped portrayals of Terra's Earth classmates (the pretty popular girl, the big dumb jock, both of whom show up in a superfluous graduation scene at the start of the book), I felt I was looking into a teenager's mind--not the teenager that is the novel's protagonist, but the hypothetical teenager who concocted large portions of this story.

To be honest, the entire novel feels stuck in a teenager's mind. It's filled with ideas but few details, characters but little characterization, dialogue that is meant to be hard-hitting or witty but lacks any sense of flow or nuance. It reminds me of the sort of writing I did when I was about thirteen. It was imaginative and novel-length, yes, but nothing was honed. There were plenty of words, but there wasn't a lot of care put into finding the right ones, or stringing them in the right order. Characters would often be built to fill roles, not built to be people. The Rule of Cool--wherein logic is set aside for the sake of scenes aspiring to movie trailer-level awesomeness or humor--always won. Dialogue was often the result of trying to forcibly replicate television scenes, without understanding their context or voice. This created rigid, laborious exchanges that felt more like two people trying to monologue past each other, adding details that had no business being there and forcing unrealistic responses for the sake of having emotion somewhere.

I actually see a lot of my own unpublished book in Aeon Legion: Labyrinth. It takes me back to the passion I had in middle school for creating my own world and filling it with characters and scenes I thought were cool, and watching as the word count rose to something that could actually be considered a novel.

If this were an artifact of a friend's childhood, I would probably be telling them how cool it was that they made something this expansive in their free time at such a young age. But there's a big difference between writing something this rough for fun and writing something this rough for profit. And there's an even bigger difference between writing something this rough for profit as a child amateur and writing something this rough for profit as a self-styled professional writing advisor.

That's the part that annoys me so much about this book. It's not so much that I paid like fifteen dollars for this miserable experience, it's that it's a shoddy, unedited mess of tropes and missteps by someone that over three hundred thousand viewers around the world look to for writing advice. It's sarcastic advice, of course--this is the internet we're talking about--but the end goal of his channel is to help others improve their writing, and as such he speaks from a self-appointed position of expertise. But either he didn't bother taking any of his own advice into consideration, or he did and still came up with this monstrosity. And I honestly don't know which is worse.

Beaubien's book, if I haven't explicitly mentioned it yet, is self-published. He actually has a video about choosing between traditional and self-publishing routes. Here's a screenshot from that video:

Note "Great fit for the multi-talented do it yourselfers".

Note "No one to tell you 'no'".

I can't help but feel like his pros and cons list is heavily weighted towards self-publishing, and that he views traditional publishing as more of a manufacturing line rather than a place for visionary artists. His focus on the self-published route allowing for full creative control, and being a great fit for those skilled in multiple disciplines, suggests he considers himself someone with great vision that shan't be stymied by the interference of other voices. Therefore, even if he were to hire outside experts to assist with editing, art, etc., he would still want to be in the driver's seat creatively.

However, it came to light during one of our book club meetings (thanks to someone's dive into Beaubien's personal website) that Beaubien chose not to hire an editor after all. Instead, he supposedly spent a couple years teaching himself how to be an editor, and then wore that hat himself. Because, as the label clearly states, he's a "multi-talented do it yourselfer".

Go back up to the pros/cons list. Note "A Quick Honest Thoughts".

Here's my quick, honest thought(s): Aeon Legion: Labyrinth is the single most poorly-edited document I have ever read. And I'm including handwritten letters from kindergarteners.

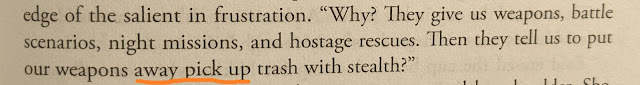

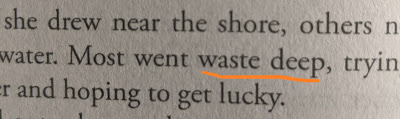

Pick a number between 1 and 394, and on the corresponding page I will show you at least three missing commas, two missing hyphens--or, if you're lucky, one of these gems:

Fun fact: the only non-compound English words to contain the letter pairing "lh" are "silhouette" and "separatelhy".

Why use a blade to scratch off your emblem when you can just stiffen it instead?

This sentence contains the rare silent "and".

I'm nowhere near qualified enough to comment on the sociological implications of this typo.

Strike one!

Strike two!

Strike three, you're out! What a waist.

There's also this baffling formatting mistake, where chapter 33 switches from the novel's consistent justified alignment to being align left, only to finally correct itself nine pages later:

(This would be easier to see if I were able to produce larger excerpts, but you'll just have to trust that the left side is page 367, and the right side is page 376.)

I could literally do this all day. There's dozens of problems like this, a handful of which have been fixed in the digital edition of the book (which, considering my physical copy was printed in March 2021, only serves to confound me more). Since this dissection is already exhaustingly long, I'm going to end here, on what might be my favorite phrase in any written work:

This is poetry.

I hope those excerpts illustrate how challenging it was to read this book, not just in terms of how bad the story and characters are, but strictly from a comprehension standpoint. (I mentioned during one of our book club meetings that I wanted to drive up to Beaubien's house and drop a bucket of commas on his front lawn, because my God does the man need them.)

Now, at this point, you're probably wondering what left there is to cover. If you are, that's because you've forgotten that we aren't even halfway through the novel. No, we abandoned Terra in the middle of her initiation for a very long tangent, and we should probably get back to her before she, I don't know, sits still or something.

So, as I was saying, Terra continues to be dragged through ever more tests, the highlight of which is an automotive race that Hikari--you know, the girl from feudal Japan--wins on her first try (without hardly touching the "break" pedal). We get hints at the larger world Beaubien is trying to build through a handful of vague-yet-intrusive name drops--the Kalians (some other time-exempt faction), the Faceless (some other other time-exempt faction), the Forgotten Guns (some other other other time-exempt faction)--and eventually move into a bout of survival in the Cretaceous Period. The tiros are dropped in with nothing but their shieldwatches and their wits, and have to find a way to survive in the era of dinosaurs.

Except, like, Beaubien hardly touches on the dinosaurs at all. They're not majestic wonders a la the opening of the gate in Jurassic Park, nor are they frightening monstrosities in the style of kaiju. They're hardly anything at all, in fact, because the author instead sidelines them in order to set up a Kalian military base that captures Terra and several of the other tiros. Once restrained, Terra is subjected to intense interrogation techniques to gain information on Saturn City. But, being the dull grey boulder she is, Terra remains silent.

At this point, the captain of the Kalian forces reveals himself to be Cerberus, because the whole survival trial was--gasp--a trick! They never left the Academy at all. The "Kalian forces" were just Academy employees in disguise.

Effectively, this means Terra's principal just cosplayed as an enemy soldier and subjected his own students to military interrogation tactics and torture. Cool. Cool cool cool.

Once the tiros have gone through several months of training and been narrowed down to the best of the best (read: the only named recruits in the book), it's time for their final test: the titular Labyrinth.

The Labyrinth is broken into twelve trials for the same reason there are twelve Legendary Blades, twelve sectors in Saturn City, twelve towers around the Labyrinth, twelve pillars in the Academy's archive room, twelve soldier ranks in the Aeon Legion, and twelve cohorts of Legion soldiers: Beaubien can only hold a single descriptive trait in his head at one time. A clock has twelve hours on its face, so everything in this magical land of time must be subdivided by twelve. There is no other option because I suspect he literally cannot comprehend the idea of using multiple simultaneous motifs for the same broad topic. My other friends groaned at the recurring elemental traits exhibited by the main characters, but I was positively livid about the overuse of the number twelve.

Anyways, Terra and company dives headfirst into the Labyrinth, where she quickly finds herself face to face with Samael. You remember Samael--former leader of the Forgotten Guns, who's released from the Saturn City prison Tartarus once a year to play Joker and kill as many tiros as possible while uttering witticisms like "I'm Santa!" and "Don't make me sing!" just to prove how crazy he is? Yeah, me either. Terra is able to escape while Samael is villain monologuing, and we never hear about him or the Forgotten Guns again.

So, before we go any further into the Labyrinth, it's important to note one thing: Beaubien didn't have twelve good ideas for trials, but was insistent on using his holy number as much as possible. In fact, one of the "trials" is just the fact that there's a time limit--144 hours, or twelve squared, kill me please. That's not a trial, that's a parameter. That's like saying the SAT consists of two halves: finishing the SAT and finishing the SAT in three hours. One of those is just a clarified version of the other. So what Beaubien actually has are eleven trials and a rule he renamed to fit his compulsion for round dozens, seemingly at my expense.

There's also the Trial of Storms, which from what I can tell is walking through rain without an umbrella; the Trial of Blades, which is identical to the earlier Trial of Blades duels found all throughout the earlier sections; and the Trials of Truth and Fear (touted as "the only trial Kairos failed"), which are sandwiched together into a single dream-like montage prefaced by a note from Cerberus saying it will be no problem for Terra. And, sure enough, she is completely unaffected by the visions of dead friends and dark memories because she's a rock, and rocks can't feel. So, by extension, the reader doesn't feel anything during this sequence either, meaning the two trials are an utter waste of time for both Terra and the audience.

So, if you take out the two trials that Terra is entirely immune to, the trial that has existed for half the book, the trial that's actually a rule, and the trial that is weather, there are only seven real, unique trials within the Labyrinth. Of the remaining seven, one of them is just Terra proclaiming why she wants to be part of the Aeon Legion to Cerberus, and another is cut short by the plot, which we'll get to soon. That leaves five full trials that will actually test Terra's abilities. We've already touched on the Trial of Survival with Samael, and the Trial of Keys is a test of intelligence wherein Terra has to solve a code keeping the gate to the next trial locked. The Trial of War is an assault mission, where several of the tiros team up to get through an enemy base, sort of mirroring the woefully dinosaur-free mission from earlier. This is the only other time in the book where Terra's climbing ability matters, because she scales a wall during this trial and I guess that's useful.

Two trials left to discuss. Let's move on to the Trial of the Beast.

If you're familiar with the Halo franchise, you'll know what one of my book club members meant when he said this section felt like the Gravemind.

The tiros fight the Manticore haphazardly, and Terra shows a level of control over her shieldwatch abilities that is unbelievable. Like, literally, I don't believe that she is as capable as she appears in this chapter. She manipulates the speed of time not just around herself to make her move faster than the Manticore, she releases kinetic energy in bursts in order to safely absorb the monster's attacks, all while dodging a hundred-foot insect that won't shut up about being the next step in life's evolutionary track. Zaid is mortally wounded, but because Beaubien has no control over tone I straight-up didn't notice for several pages. The group eventually escapes, and with Zaid's death the book is at 50% mortality rate for people of color.

I've been discussing the trials of the Labyrinth a bit out of order, because Zaid's death in the Trial of the Beast is supposed to be the emotional centerpiece of the whole operation. Unfortunately, Terra's bond with Zaid never came across as much more than a working relationship that--when coupled with Beaubien's unfortunate monotony--means we felt nothing at all when Zaid died. He shows up in the Trial of Fear, yes--but only as part of the montage, of equal weight as Cerberus's mere existence. It's a throwaway death meant to service a throwaway trial in a throwaway book.

And with that, we come to the only trial I haven't mentioned: the Trial of...

...uh...

Okay, I've been flipping through the six Labyrinth chapters of the novel for the last two hours, and I cannot for the life of me find twelve trials. I've counted, recounted, written them out... there are only eleven. But that can't be right...

...can it?

(You weren't expecting a courtroom drama when you started reading this, were you?)

After taking two days to study the text and confer with the rest of my book club, I am ready to present my findings to the jury.

Exhibit A: Terra enters the Labyrinth on page 288, at the very end of Chapter XXIV. Chapter XXV, called "Labyrinth", begins immediately after.

Exhibit B: On page 290, Terra is notified of the Trial of Keys, immediately followed by the introduction of the timer, AKA the Trial of Time.

Exhibit C: Page 293 contains the statement "Trial of Keys complete", as well as "Trial of Survival beginning." However, one other message is also presented to Terra: "Two of twelve Trials completed." Because the Trial of Time countdown is still counting down, it remains incomplete. Therefore, the completed trial that isn't Trial of Keys must have already occurred. We need to go backwards.

Exhibit D: Prior to entering the Labyrinth in Chapter XXIV, Terra observes the Labyrinth from above. The Labyrinth is actually twelve(!) round salients (constructed space used for Academy training) that form a ring and are connected by ever-changing spokes as they rotate clockwise(!!) around a center point. The salients are not explicitly stated to each correspond to a single trial, but during the succeeding chapters Terra only moves between salients upon completing a trial.

Now, at this point, I was thoroughly confused. We have twelve areas that are, through textual evidence, designed to each contain a single trial. And yet we also have the Trial of Time, which exists outside of any physical realm and therefore cannot be given its own salient in the Labyrinth. This is strange, but not what we're gathered here for.

Exhibit E: On page 278, Cerberus speaks to the tiros and tells them "You will face twelve trials within [the Labyrinth]." He also says "The Labyrinth must be completed within one hundred forty four hours", which seems to suggest that the timer is not one of the twelve trials. Again, confusing, but we still haven't found the Missing Trial.

Because, it turns out, it is on page 277, prior to Terra entering the Labyrinth, prior to seeing the twelve salients, prior to Cerberus stating there are twelve trials within the Labyrinth. It comes when Cerberus tells Terra that her score sucks, and she's not qualified for the Labyrinth. To this, Terra of course says "I wanna do it anyways," and Cerberus goes "You've passed the first trial, everything's made up and the points don't matter!" This conversation is so incredibly similar to the Trial of Worth, where Cerberus asks Terra why she wants to join the Aeon Legion, that I had completely forgotten about it being a separate scene.

...so, that's it. Mystery solved, I guess.

Or is it?

If Terra demanding to still enter the Labyrinth counts as a trial, that means Cerberus was lying, and there are only eleven trials within the Labyrinth, with the twelfth taking place prior to even being briefed on the Labyrinth. But if that was in fact the first trial, then every student, regardless of their points standing, would have had a similar conversation prior to being prepped for the Labyrinth, meaning everyone would know there are only eleven trials left. In that case, Cerberus was lying for absolutely nobody's benefit.

Unless, of course, only Terra was given the pre-Labyrinth trial. Perhaps there were twelve Trials for everyone else, but she got a free pass and only had to participate in eleven. That would mean there is only one unused salient (the one corresponding to the Trial of Time, which has no location), instead of two (the second belonging to the missing trial). If that were the case, however, surely it would have come up when Terra was teaming up with Roland, or Zaid, or Hikari, who would have been so secure in their pre-Labyrinth standings that they would surely have had to go through whatever this mysterious twelfth trial was.

On the one hand, Cerberus is a known liar, as evidenced by the numerous tests-within-tests I've already touched on. On the other hand, the Academy is practically tailor-made for Terra to succeed, and giving her a free pass would be entirely within the realm of possibility for this impossible school. On the third hand (which I wish I could refer to as the "second" hand for a bad clock joke), Beaubien has demonstrated himself to be a terrible writer with little structure, continuity, or logic, and I think he just confused himself and gave up.

So, with all that being said, here is the official, ordered list of the twelve Trials of the Labyrinth:

Glad we got that sorted out so cleanly.

So anyway, the twelfth trial is about to begin when the Nazis attack. Hanns, who for the last while has been imprisoned in Tartarus along with the other time criminals, has helped stage a break-out, and things are popping off in Saturn City. Terra confronts Hanns, who sees how much she's grown (even if the readers hardly get any sense of her development over the course of the book). They fight, and Terra eventually has him dead to rights, pointing Zaid's aeon edge at his throat.

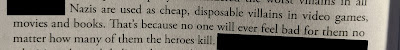

Now, being a young adult novel (which, again, this book totally is), you know Terra isn't going to kill Hanns, even though he's a Nazi which literally should only exist in stories to be destroyed. I mean, look at this Terra quote from earlier in the book:

This is your Get Out of Jail Free card, girl! This is literally the one sort of person you're supposed to kill.

But nooo. Instead, she does the "heroic" thing of letting him go, and tells him that if she ever encounters him again, she'll drag him to Tartarus herself.

You know, Tartarus. The prison he literally just escaped from. Her big threat is to put him in the prison he's already figured out how to beat.

Whatever. It's been like five pages since the last plot twist, so we need to add in another. A figure wearing a Kalian mask (though how the reader would have recognized that without being told at this very moment what a Kalian mask looks like, I have no idea) approaches, and is soon dueling Cerberus. The masked figure calls themself Exile, but eventually is revealed to be--collective gasp--Kairos, Silverwind's beloved lost squire who became a Legendary Blade but was presumed dead! Who would have predicted that?

More importantly, who would have cared? Kairos's purpose in the story, ostensibly, is to draw a comparison between Terra--the completely ordinary girl with nothing but a dream of greatness--and the star pupil who became everything Terra wanted to be, but succumbed to evil or something. (Her goal is apparently to kill time travelers because they damage the spacetime continuum, and removing them will preserve time for everyone else, though whether that's a personal vendetta or one shared by all Kalians I don't know or care.) However, in practice, previous mentions of her serve as setup for a twist that doesn't actually bear any weight. Kairos disappeared long before Terra was even aware of the Aeon Legion. She has no connection to Kairos besides them both sharing a mentor, but even that connection is tenuous at best thanks to Silverwind's aloof nature resulting in her disappearing for dozens of pages at a time, and Terra spending a collective... maybe six hours with her across three or four scenes? Kairos is obviously Beaubien's reward to himself for developing such an extensive history for his world, rather than a payoff for the readers in any meaningful way.

Kairos eventually kills Cerberus and runs off shortly after Silverwind arrives on the scene, begging to see Kairos's face one last time. After Kairos is gone, Tartarus has been secured, and Saturn City cleaned up, our three remaining named tiros are inducted into the Aeon Legion. Hikari receives a blade forged in intense fire (of course), Roland's aeon edge is etched with wavelike grooves (of course), and Terra is given Kairos's old blade, which had been literally stabbed into the ground as a memorial (OF COURSE). Terra thanks Silverwind for everything (or, in terms of what Alya actually did besides say "be my squire cuzz I'm bored", nothing at all), then goes home to visit her parents.

You know, the ones who she had told at the start of all this that she was going to be a time cop.

But they now think she is going to college or something? They ask her how classes are going, and she mentions meeting a German guy that she thought was nice... you know, until it turned out he was a Nazi. The whole scene is enormously confusing, and makes me wonder if the Legion has some sort of unmentioned Men In Black-style memory device that they used on her parents, and Beaubien just neglected to mention it. Either that, or he realized how insane it was for Terra to casually tell her parents about the existence of time cops, and retconned it within the same book without bothering to just go back and fix the original scene.

This is the end of the main story, and there are still a lot of things I didn't touch on.

Things like Cerberus apparently having multiple personalities.

Things like Alya Silverwind pulling Terra from her classes to go hunt more Nazis.

Things like a single flashback chapter over two hundred pages into the novel to cover Terra's past as a victim of bullying, the only scene in Terra's entire story that isn't in her present.

Things like Delphia, the girl who Terra stays with when she first arrives in Saturn City that isn't mentioned for the middle 250 pages of the book and only shows up after Terra graduates to remind us that she existed in the first place, but has no emotional or story connection to anything else in the book.

Things like a guard in Tartarus dismissing a Jewish prisoner's hatred for the Nazis by saying, and I quote, "We can't possibly keep track of every group that hates each other!"

Things like Hikari inexplicably deciding Terra is her worthy rival, despite Terra still being atrocious at just about everything the Academy throws at her.

Things like this passage that, if handled by a better writer, might come across as something other than the author elbowing us at how he progressive he is by bucking trends and writing characters that defy stereotypes, while simultaneously revealing his own biases by making them notable enough in his head to actively write against them:

Yes, it's sarcastic. But also, it isn't. It makes me wonder how much of this whole endeavor is genuinely misguided self-confidence, and how much is projecting that same confidence as a mask.

The book ends with an epilogue where the Singularity Thief, who had no bearing on the main plot, reports to the Time King, who had no bearing on the main plot, about Terra being the key to the Legacy Library, which had no bearing on the main plot. I don't know what to make of this section, and since it's been five years since the publication of this book with no word on the sequel, I don't think Beaubien does, either.

Beaubien's own website contains a place for him to update his fans on the progress of various projects. This is its current state as of May 2021:

It appears at first glance that he's fairly far along with the second volume in this series. However, this doesn't tell the whole story. While I don't know what "honest thoughts video" he's referring to, I did find the "Terrible Writing Advice on Comic Relief Characters" project that he had most recently finished. It was published over two years ago.

This means we have no way of knowing just how much progress Beaubien has made since mid-2019, when he was presumably 40% through the sequel's second draft. My suspicion is the book is still languishing in this unfinished state. The size of his YouTube fanbase indicates to me that he makes a lot more money posting videos than he did self-publishing Aeon Legion: Labyrinth, so it would make sense that he puts the sequel on the backburner.

As someone who has put sequels on the backburner, however, I do have a further suspicion that the sequel will never see the light of day. Unlike Terra and co., Beaubien must adhere to the laws of time, and the further away you get from a project the less you tend to feel towards it and the more unlikely it becomes that you ever return to it.

I can say for certain, however, that even if Aeon Legion: Legacy Library eventually does surface, you could not pay me to read it.

Well, I guess my friend was right about one thing. There was quite a bit to talk about.